In the first post in this series, I discussed the long-term low inflation that we have experienced here in US for the last few decades. This had sparked intense discussions as to why we did not see a rise in inflation, even under conditions that historically would be considered pro-inflationary. These include the boom times of the late 90’s and the very low unemployment state of the late 2010’s. Economists offered a variety of explanations for this. Let’s take a look at some of those.

One of the most commonly offered reasons for the chronic low inflation has been globalization. This started about 20 years ago when digital technologies, better transportation infrastructure, and expanding trade deals between counties allowed companies to shift production to low cost areas. Think about all of the textile, toys, and electronics made in China. Or, IT development and support jobs in India. What that meant was that companies could lower their production costs and a tight employment market in the US did not force them to raise wages, since they could shift those jobs overseas. Also, cheaper overseas production meant lower prices for consumers.

Another salient argument for low inflation in the US has been the increased automation seen in many industries. This has been increasingly made possible by software, data, artificial intelligence, and other emerging technologies. Automation lowers costs for companies, especially labor costs, which are often the companies’ highest expenses. This, similar to globalization, serves to keep wages low for labor and prices low(er) for consumers.

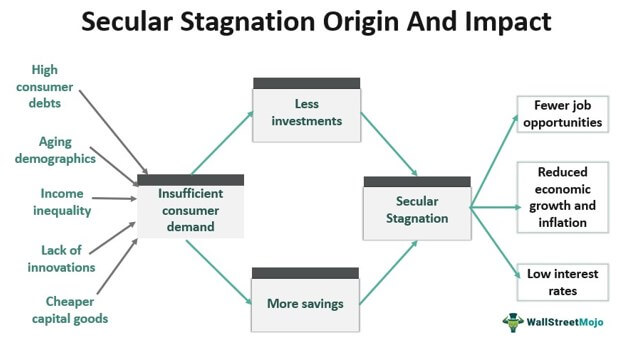

Another key explanation offered by many economists has been secular stagnation. What is that, you ask? In short, it postulates that given some significant macro trends such as the aging population and the nature of new industries such as the internet and software that require less labor than before, the aggregate demand has dropped in the economy. The aggregate demand means the total demand in the economy for all goods and services. If the population is getting older and the labor participation is dropping, then the overall spending power of consumers drops. If companies need less labor to produce their goods and services, it lowers the pressure on having to raise wages and prices.

There are other explanations offered by economists such as de-unionization that have been debated for some time.

So, what does the rising inflation now mean for all of these long-term trends (or explanations of possible trends?) Does it mean that these explanations were wrong and inflation was always lurking in the dark, waiting to pounce under the right conditions?

let’s examine that in our next post.