Since we are tackling one of the most discussed economic (and political!) issues of the day and how its re-emergence after many decades is scaring everyone, paying close attention to historical benchmarks is quite informative. We spent some time discussing the potential reasons for the low inflation in US for the last few decades: globalization, automation, secular stagnation, de-unionization, and more. The question that I posed at the end of my last post was: Have any of these long-term forces changed? Are they weaker because of the pandemic? Is any of them gone? or, was inflation always hiding in plain sight?

To answer those questions, we need to take a hard look at what is happening in the labor markets, where we are seeing significant wage gains (finally!) and consumer products and services, where we are seeing unexpected price increases on everyday items like coffee and used cars. A fundamental question to ask here is since the price of everything is a function of supply and demand, which of these two sides of the equation has been disrupted? Is the demand way up and thus causing supply shortages? or, is supply lower than usual and thus the unmet demand is driving up prices?

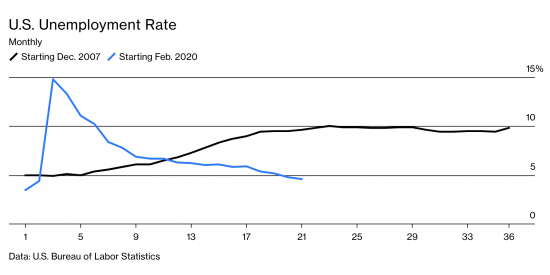

In the labor markets, the pandemic has proven to be quite a disruptive force. When the pandemic started, many people were laid off, chose to quit, forced to stay home and work remotely, or left due to childcare issues or fear of falling ill. So, the supply of workers definitely shrank, but that was not a big issue when the entire economy had slowed down significantly. People were staying home and spending far less than they usually do. This meant that businesses could operate with less employees and the lower demand mean lower prices, if anything. This was especially possible since the companies had a smaller payroll with the pandemic. Fast forward to now, the economy has re-opened and even though the pandemic is not over, people are back out there shopping and doing things. They also have the benefit of having received government money that they did not entirely spend when they were staying home.

Well, businesses now need to keep up with this demand and need their employees back. But, there are not as many employees out there as before the pandemic. Why, you ask? Because some of the changes to the labor market that happened due to the pandemic will not be temporary. A group of older people chose to retire for good due to the pandemic. Others have left the workforce because of child care issues or fear of illness. Still, others are quitting at high rates since they see the opportunity to get higher paying jobs with all of the demand out there and the labor shortages. This is pushing wages up and when wages go up, companies start increasing prices for their products and services to recoup these increased expenses. So, in the labor market, we have lower supplies due to the pandemic and rebounding demand, leading to rapid wage gains.

On the products and services side, some of that rebounding demand fueled by increased savings (from staying home for months!) and government payments, coupled with disruptions to the supply chain worldwide is causing imbalances between supply and demand. The well-publicized shortage of microchips is affecting auto production, computers (I’m having to wait for more than 6 weeks to get my new McBook!) and other high-tech items. Congestions at ports is causing issues with the supply of commodities such as coffee, fruit, and other consumer staple items. The main point to keep in mind here is that there is not a long-term major shift in the demand for coffee or used cars. There’s a rebounding short-term demand and short-term supply shortages.

So, what does all of this mean? Will all of this inflation, then, evaporate in the coming months or year and we’re back to long-term low inflation? My current position on this, having examined the data over the last couple of months, is that most of the current inflation will gradually resolve since the long-term drivers of inflation have not significantly changed. Our demographic issues that were considered a major factor in low inflation remain intact. Long-term growth rates in the US economy, which determines how much the household wealth increases over time, is not forecast to change dramatically (or, is it?, more on this in the future. There are certain things happening that have increased my optimism for the long-term prospects of the US economy.) And, there is not a projected long-term shortage of the many of the items that are currently experiencing issues. Unfortunately, transitory inflation can hang around for a while, as shown in the figure below. In two of the more severe bouts of inflation in the US economy in the last 100 years, inflation stayed around for 3-5 years.

What may end up being sticky from the current inflation are the increased wages of the American workers. Generally, wages are far more sticky than the price of goods and services. Is this good or bad? Well, mostly good since higher wages will mean higher standard of living for Americans. However, some of the higher wages will mean higher prices for consumers. I will expect most of the inflation to subside in the coming year(s?) but long-term inflation could trend up slightly from where it has been for the last few decades