In the last post we talked about the difficult task facing the Fed with interest rates. If interest rates are raised to cool off excess demand and at the same time the short-term drivers of inflation subside on their own (people spending their savings from government payments, supply chain issues resolving, and geopolitical tensions easing) then will we have a situation where the economy tips into recession? A combination of the Fed actions and natural economic forces can cool off demand too much and cause a recession.

This is an ongoing debate in the economic and investor community and there are opinions on all sides. Many people feel that the Fed did not act quickly enough last year to prevent the current inflation and now that those inflationary pressures might be easing on their own, the Fed is taking action too late and can cause an economic slowdown. Others feel that some of the inflationary pressures are not temporary, such as wages, and if the Fed does not act now, we can see a wage-price spiral. This is when companies compete for talent and raise wages to attract workers and then raise prices to protect their profits and you get rising inflation. Long-term policies that improve supply of talent, such as immigration reform, education, easing restrictive licensing rules, and child care assistance can ease this longer-term driver of inflation.

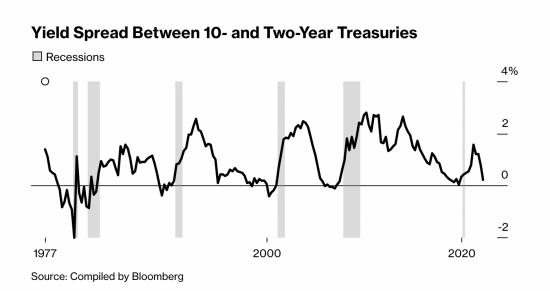

One of the indicators that people have come to rely on for predicting recessions is the yield curve. This is the difference between long-term and short-term government bonds. Generally, the longer term bonds pay higher interest due to the longer maturation and the increased risk of default that comes with that long maturity. In normal times, you almost always get a higher yield on longer-term bonds (government treasuries or corporate bonds.) If the shorter term treasuries start to have a higher yield than the longer term treasuries, it can be an indication of looming recession. The logic is that when investors expect short-term trouble in the economy, they pile into the longer-term bonds and when the demand for longer-term bonds increases, their price goes up and their yield falls. If it falls below the short-term treasury, it could indicate that a lot of the sentiment out there is negative toward the short-term economic outlook. Bonds and stocks are competing investment classes and an increasing appetite for bonds over stocks means that the investors are becoming pessimistic about short-term returns on equities.

In the recessions of the last 60 years, in every case they were preceded by an inverted yield curve (the difference between the yield on longer-term treasuries minus yield on short-term treasuries became negative.). Important to note that not every inversion has predicted a recession and brief inversions could be due to other factors and not necessarily predict a recession. Also, an inverted yield curve does not mean recession is a couple of months off. A Credit Suisse analysis shows recessions follow inverted yield curves by an average of about 22 months.