China’s rise as an economic power has been marked by tapping the potential of a large, mostly under-used population. It moved hundreds of millions of people from rural to urban areas and became the production factory for the world. This has increased the GDP per capita in China to around ten thousand dollars. This is a large jump given where China has been in the last few centuries. It was, in part, result of moderate liberalization of their economy, allowing private ownership, investments, and participating in the international economy. However, while China was using the untapped potential of a large workforce and growing its economy, policies already in place such as the one-child policy were slowing their population growth, resulting in an aging workforce. This, along with other challenges, may make the ascendance of China to become the world’s largest economy anything but certain.

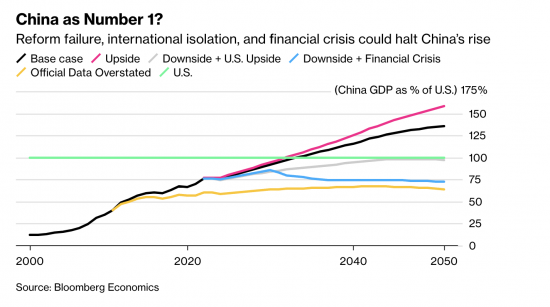

Last year, in an article in Bloomberg Businessweek, there was an examination of some of the challenges that the Chinese economy faces in the decades to come. You can see from the graph above that the current low fertility rate can mean fewer workers and lower growth rates. China could offset some of this by pushing back the retirement and pension age. Still, in spite of the rollback of the one-child policy and plans to push back the retirement age, demographics are expected to be a drag on China’s long-term growth.

Another key factor that can slow down China’s growth is that although strong investments in infrastructure was a key driver of China’s growth in the last few decades, it is now clearly showing signs of diminishing returns. Meaning that even if China continues to invest heavily in infrastructure, it can not be expected to show the same impact on their growth since key returns have already been realized in foundational investments. Also, it is clear that some of the investments were not well-spent and have created overcapacity in key sectors. As Bloomberg Businessweek wrote ” With the labor force set to shrink, and capital spending already overdone, it’s productivity that holds the key to China’s future growth. Boosting it, most Western economists think, requires action such as abolishing the creaking hukou system (which ties workers to their place of birth), leveling the playing field between state-owned giants and nimble entrepreneurs, and reducing barriers to foreign participation in the economy and financial system”

There is still low hanging fruit for China for boosting productivity. Its economy is only 50% as efficient as US economy so it has not run out of room to improve things in this area without undertaking major reforms. However, it only gets harder from here on out to improve productivity while holding on to a system that favors state-owned enterprises and allocates capital based on your loyalties to the communist party. In order to boost productivity, they will need much better trained workforce and advanced technologies. Historically, advanced technologies are the result of investments (usually in public sector to start with) and institutions that can make something out of those investments. China clearly now has the financial resources to invest in innovation, but given the path they are now choosing of taking a heavier hand to the private companies, combined with public institutions that are not yet very sophisticated, it is hard to see how they can catch up technologically.

China has benefited from the international flow of ideas and technologies in the last three decades. Its increasingly aggressive stance toward its neighbors, its treatment of Hong Kong, poor human rights record, and COVID has meant that increasingly the world wants to do less business with China, and not more. Even if the leaders of China don’t realize how this might impact its ascendance in the world, they will in the next few years.

Next, we will look at China’s fragile financial sector and how it may be ripe for significant disruptions that can serve as a major blow to their economy.