Every year, the US spends more than $400 billion on public infrastructure. But annual infrastructure funding routinely falls short of capital and maintenance requirements, contributing to deterioration of the country’s infrastructure assets.

In 2017, the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) gave US infrastructure a grade of D+ and estimated that an additional $2.1 trillion in infrastructure investments is necessary between 2016 and 2025 to meet demand and reduce negative impacts on the economy. What’s more, ASCE has calculated that inadequate infrastructure funding could cost the nation almost $4 trillion in GDP and a loss of 2.5 million jobs through 2025.

Infrastructure assets are costly long-term investments. Many state and local governments that are responsible for delivering them are facing tight budgets and finding it challenging to deliver all the infrastructure they would like to. Bridging this infrastructure gap is a complex interdisciplinary challenge that requires creativity and innovation in the planning, funding, financing, construction, and operations of infrastructure assets.

Government investment has the potential to boost long-run productivity, wages, standards of living, and international competitiveness and to help redress long-standing sources of inequality. Government investment also provides public goods and services that the private sector tends to underproduce. For example, public funding for research and development has large, positive social externalities that private firms do not take into account when making decisions about how much to invest. Unlike public consumption, which often focuses on smoothing business cycles, government investment is made with an eye toward long-term economic goals.

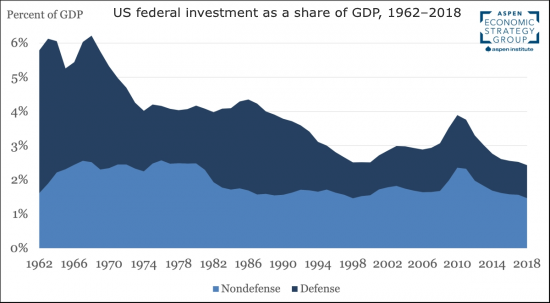

In 2018, the US government invested less as a share of the economy relative to any other year since the early 1960s (Figure 1.) This fact is especially striking since government debt as a share of the economy reached 104% in 2018, nearly surpassing the previous peak during World War II. With the exception of a temporary increase in funding for infrastructure projects and investment in response to the Great Recession, the recent run-up in federal debt has largely financed public consumption rather than investment.

Figure 1 – US federal investment as a share of GDP, 1962–2018

Figure 2 breaks down nondefense investment into its three primary categories: physical capital, education and training, and R&D. As a share of the economy, the US federal government invested just under 1.5% of GDP across all three categories in 2018. This is well below the historical average of 2% of GDP per year and is the second lowest level between 1962 and 2018.

US investments in physical capital peaked in the 1960s and 1970s at 1.1% of GDP, a period which included the construction of the interstate highway system. Physical capital investment increased temporarily to 0.9% in 2009 and 2010 due to investments associated with the passage of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA).

Figure 2. US federal nondefense investment as a share of GDP, 1962–2018: physical capital, education and training, and R&D

All of this is very important and consequential for America’s future. Public capital (infrastructure) and technological progress (driven by R&D) can play an important role in stimulating both long-run economic growth and labor productivity (and thereby long-run wage growth). Increasing the amount of capital available per worker hour, known as capital deepening, and technological progress are important drivers of labor productivity, along with human capital investments. Public investments that raise the total amount of capital available per worker and accelerate technological innovation through investments in R&D fuel productivity growth and therefore long-run wage and economic growth

So, no surprise that we have seen wage stagnation and and declining prospects for the middle and working class families